Can (Or Should) Open Source Be Restricted To Ethical Practices?

Relations between American corporations and the Chinese government have become even more strained this week over the continuing Democratic protests in Honk Kong and the way China believes those businesses are supporting the protestors. The Chinese government has long considered any form of demonstration in support of Hong Kong’s autonomy from China as a threat to its national sovereignty and strongly discourages any expressions of solidarity or support with the demonstrators, whether it be from inside or outside their own borders. On Wednesday morning, China’s state media issued a warning to Apple to refrain from aiding protestors in Hong Kong in determining the whereabouts of local police with the company’s HKmap.live map mobile application. The warning is in keeping with China’s longstanding policy of restricting technology and the way it is utilized by its own citizens (social media sites like Facebook and Twitter are blocked in China). Even before the protest in Hong Kong erupted, the trade war between the United States and China over what the U.S considers the theft of intellectual property from American technology companies was in full throat - all of which is to say that the ways in which technology is being co-opted, disseminated and implemented is an issue all over the world in 2019. Along those lines, programmers and designers are worried about the ways in which the technologies they’ve developed are being used.

Coders in particular are increasingly wary of the ways their work is being implemented. Last year Google opted not to renew a controversial contract with the Department of Defense to help develop AI-based tools for analyzing military drone footage that expires (or expired) at some point in 2019 after internal pressure from its own employees (as well as external pressure) forced the company to reconsider the ethical implications of participating in such a project. In April of 2018, over 3,000 Google employees signed an open letter to the company’s CEO asserting that “Google should not be in the business of war.” The Google example is just one of a number of instances in which software was used for purposes which its designers never intended. In this case, the company conceded to the demands of its workforce – but what if the programming being co-opted for unethical purposes is open source? How can the use of open source code be regulated when it’s freely available for all to use?

Programmer Seth Vargo recently learned that code he’d written was being used by software development company Chef, which has an ongoing IT contract with US Immigration and Customs Enforcement, otherwise known as ICE. After trying to get in contact with the company’s executives for three days with no success, Vargo decided to remove his code from the open-source platform GitHub. “As software engineers, we have to abide by some sort of moral compass,” Vargo espoused. “When I learned that my code was being used for purposes that I personally perceive as evil, I felt an obligation to prevent that.” While his principled stance will be considered admirable by many, it truthfully didn’t do much to address the perceived problem – while Chef’s systems were briefly affected by the removal of Vargo’s code, the company’s systems were fully operational again an hour and a half later.

Is there any recourse for ethically motivated coders? Coraline Ada Ehmke, a pioneer in the discussion of the ethical use of open source code, believes she’s created one. She calls it the Hippocratic License, and it basically states that software released under its auspices can be implemented, shared or modified for any purpose so long as it’s not used by “individuals, corporations, governments, or other groups for systems or activities that actively and knowingly endanger, harm, or otherwise threaten the physical, mental, economic, or general well-being of individuals or groups in violation of the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights.” In 2014 Ehmke penned the original draft of the Contributor Covenant, a code of conduct for open source projects that has been adopted by over 40,000 different platforms including the Linux kernel and Google’s AI project TensorFlow. The Hippocratic License is still in its infancy and has to clear several legal hurdles, as well as issues of compatibility with other licenses, but Ehmke believes it has already furthered the conversation around ethical practices in the open source community, which may ultimately be its primary contribution to the cause. Similar efforts to restrict the applications of freely available software in the past have made very little impact, and Ehmke concedes that the HL might not make much of a practical impact on open source practices. As for furthering the conversation, she’s seeing more results. The nonprofit Open Source Initiative (OSI) recently responded to the HLs central arguments via OSI co-founder Bruce Perens’ blog, despite the HL not yet being submitted to the OSI for a formal review. Although he ultimately comes down against the HL (although admittedly not against what he considers its good intentions), you could argue that eliciting a response of any kind is a positive first step.

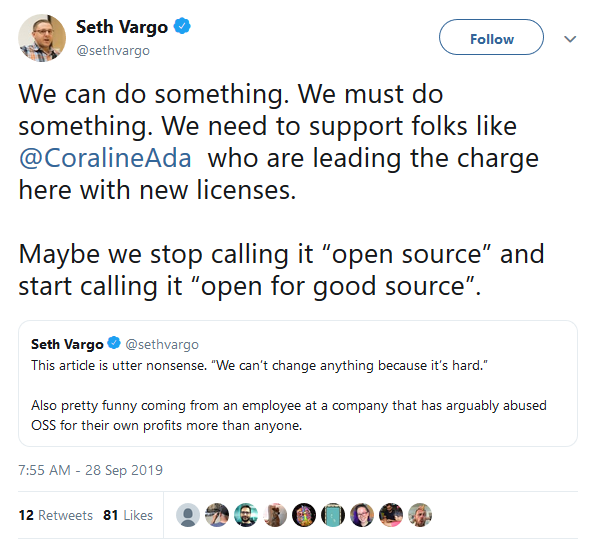

Ultimately, the solution might lie in terminology. The term “open source” itself (according to her own account) was coined by Christine Peterson of the Foresight Institute in February of 1998 to distinguish it from “free software” as it was then known, a term Peterson recollects was creating confusion over the various connotations of the word “free.” In a tweet last week, Seth Vargo argued the term “open source” might require a revision to meet the moment:

Whether merely changing the wording will have the desired effect in the open source community remains to be seen, but it will be interesting to see if the suggestion will further encourage healthy debate on the topic. Technological responsibility is a central issue in modern life, and the technologists themselves would (understandably) like their voices to be heard.